Johnson declared "war on poverty," introducing a variety of federal welfare programs, including Medicare which was initially proposed by Kennedy in 1960.

Johnson also renewed efforts on getting the Civil Rights bill passed. President Kennedy had submitted the civil rights bill to Congress in June 1963, which was met with strong opposition. But after Kennedy's death Johnson asked Bobby Kennedy to spearhead the undertaking for the administration on Capitol Hill.

Johnson also renewed efforts on getting the Civil Rights bill passed. President Kennedy had submitted the civil rights bill to Congress in June 1963, which was met with strong opposition. But after Kennedy's death Johnson asked Bobby Kennedy to spearhead the undertaking for the administration on Capitol Hill.

In March 1964, after 75 hours of debate, the bill passed the Senate by a vote of 71–29. Johnson allegedly told an aide, "I think we just delivered the South to the Republican party for a long time to come", anticipating a coming backlash from Southern whites against Johnson's Democratic Party.

Sadly, the passing of the act and it being signed into law did not end the battle for racial equality. Some white officials still resisted and used literacy tests and other barriers to stop black Southerners from voting.

SCLC had chosen to focus its efforts in Selma because they anticipated that the notorious brutality of local law enforcement under Sheriff Jim Clark would attract national attention and pressure President Lyndon B. Johnson and Congress to enact new national voting rights legislation.

As sheriff, Clark wore military style clothing and carried a cattle prod in addition to his pistol and club. He also wore a button reading "Never" [integrate], because he opposed racial integration.

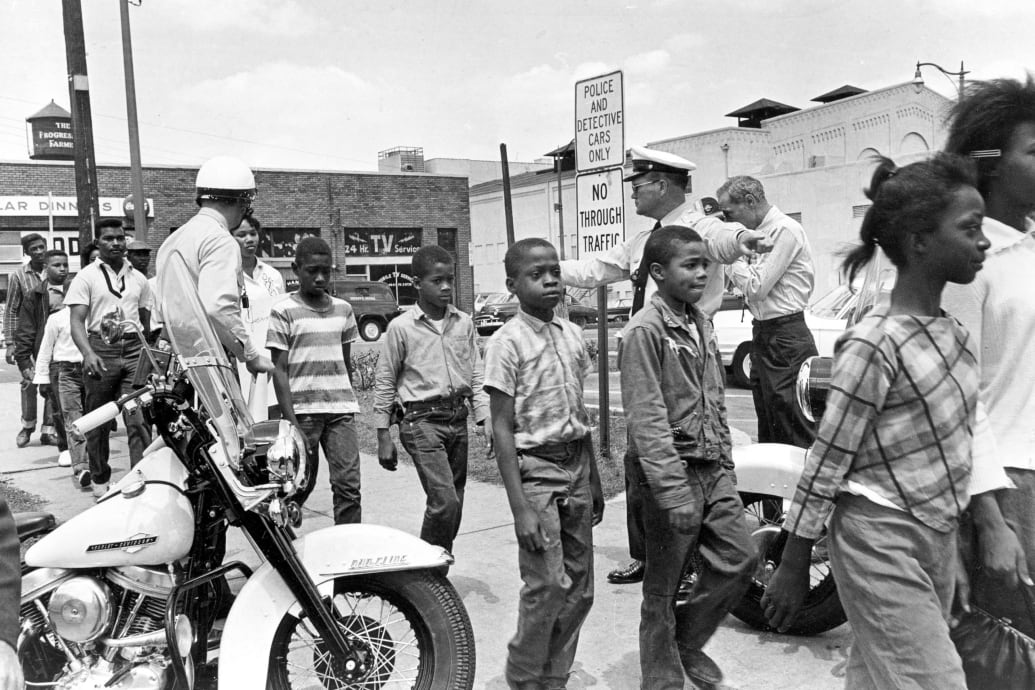

Wearing a button wasn't the only way Clark showed his contempt for people of color. He would wait at the entrance to the county courthouse and beat and arrest anyone that he deemed to be causing a nuisance. At one point, Clark arrested around 300 students who were holding a silent protest outside the courthouse, force-marching them with cattle prods to a detention center three miles away.

Another time, demonstrator Anne Lee Cooper stood for hours at the courthouse in an attempt to register to vote. Clark tried to make her go home by poking her in the neck with his club. She punched him in the jaw and knocked down. Deputies then wrestled Cooper to the ground as Clark continued to beat her repeatedly with his club. Cooper was charged with "criminal provocation" and was escorted to the county jail, and then held for 11 hours. She spent those hours in jail singing spirituals. Some in the sheriff's department wanted to charge her with attempted murder. Following this incident, Cooper became a registered voter in her home state.

Clark also recruited a horse mounted posse of Ku Klux Klan members and together with the highway patrolmen of Albert J. Lingo, they acted as an anti-civil rights force. They appeared at several Alabama towns outside of Clark's jurisdiction to assault and threaten civil rights workers.

Now back to King and the SCLC. On January 2nd,1965, King defied a local judge's orders, that barred any gathering of three or more people affiliated with the SNCC, SCLC, DCVL, or any of 41 named civil rights leaders, and spoke at Brown Chapel.

On January 15th, King and Johnson brainstormed about what strategy was best to draw attention to the fact that most black people were still not allowed to vote by the loopholes that had been put in place by local officials.

In February, the arrest of pastor, civil rights leader and assistant to King, James Orange sparked a march to support him. The march would turn out deadly.

Orange was born on October 29th, 1942 in Birmingham, Alabama. He was the third child of seven born to Calvin and Ida Robinson Orange. Calvin worked at American Cast Iron Pipe Company iron mill in Birmingham, but was fired in 1957 for union activity. Ida was very active in the Civil Rights Movement and also attended the Monday night mass meetings at the Sixteenth Street church.

Orange graduated high school in 1961 and then got a job as a chef at a local restaurant.

The Sixteenth Street church is where Orange attended his first civil rights rally, in the hope of impressing a young woman who sang in the church choir. He was late and had to sit in one of the only open pews in the front row, which had been reserved for individuals volunteering to picket local stores in the nearby downtown area. While sitting there, Orange passion was ignited by a sermon by Rev. Ralph Abernathy.

He advocated for the participation of children in the 1963 Birmingham Campaign and recruited them to take part in the controversial demonstrations known as the Children's Crusade. This public display of brutality against children by law enforcement prompted Kennedy to call for civil rights reforms.

Orange also worked to encourage fearful African Americans to register to vote and be more active in politics.

In 1965, Orange went to Marion to participate in a voter registration drive. There, Orange was arrested and jailed on charges of disorderly conduct, inciting students to participate in voting rights drives, and contributing to the delinquency of minors. After his arrest rumors swirled around that Orange was going to be lynched.

Jackson was born on December 16th, 1938 in Marion, Alabama. his family belonged to the Baptist church. He was named after his father. After his father died when Jackson was 18 years old, he took over working on and managing the family farm. He also worked as a laborer and a woodcutter, earning six dollars each day he worked. Jackson was also the youngest deacon of his St. James Baptist Church in Marion.

The marchers were fearful of what might happen to them, but they pressed on in a thin column down the bridge’s sidewalk. They stopped about 50 feet away from the authorities.

On the night of February 18th, about 500 Marion residents gathered to protest Orange's imprisonment and to pray on his behalf. They left Zion United Methodist Church in Marion and attempted a peaceful walk to the Perry County jail, which was a half a block away and where Orange was being held. The marchers planned to sing hymns and return to the church, but they never made it to the jail.

The marchers were met at the post office by the county sheriff's deputies and Alabama state troopers. The street lights went out and chaos ensued as the police began to beat protesters.

Among those beaten were two United Press International photographers, whose cameras were smashed, and NBC News correspondent Richard Valeriani, who was beaten so badly that he was hospitalized.

The marchers turned and scattered back toward the church.

26-year-old Jimmy Lee Jackson, his 16-year-old sister Emma Jean, his mother Viola Jackson, and his 82-year-old grandfather Cager Lee, ran into Mack's Café behind the church, pursued by state troopers.

Jackson had tried unsuccessfully to register to vote for four years. His mother and his grandfather had also attempted to register, also unsuccessfully. Jackson was inspired by King, who had come with other SCLC staff to nearby Selma to help local activists in their voter registration campaign. Jackson attended meetings several nights a week at Zion's Chapel Methodist Church. Jackson and his family were among those marching to support Orange and that is why they were being chased by the police.

Back to February 18th, 1965. Police clubbed Jackson's grandfather to the floor in the kitchen. Jackson's mother attempted to pull the police off she was also beaten. Jackson tried to protect his mother and a trooper threw him against a cigarette machine. A second trooper, James Bonard Fowler, shot Jackson twice in the abdomen. Jackson then staggered out of the café and suffered additional blows by the police. He then collapsed in front of the bus station.

Jackson had been taken to Good Samaritan Hospital where he told FBI officials and lawyer Oscar Adams that he was "clubbed down" by state troopers after he was shot and had escaped from the café. Later, Jackson was served with an arrest warrant by Col. Al Lingo, head of the Alabama State Police.

On February 26th, Jackson died in the hospital. Sister Michael Anne, an administrator at the hospital, later said there were powder burns on Jackson's abdomen, indicating that he was shot at very close range.

He was buried in Heard Cemetery, an old slave burial ground, next to his father. Two memorial services were held, once of which King spoke.

"Jimmie Lee Jackson’s death says to us that we must work passionately and unrelentingly to make the American dream a reality. His death must prove that unmerited suffering does not go unredeemed. We must not be bitter and we must not harbor ideas of retaliating with violence. We must not lose faith in our white brothers."

All the violence, injustice and Jackson's death sparked the Selma to Montgomery marches.

The first march took place on Sunday, March 7th, 1965. About 600 people set out from the Brown Chapel AME Church. They marched undisturbed through downtown Selma.

They then began their journey over the Alabama river by way of the Edmund Pettus Bridge. The bridge had been completed in 1940 and was named after a Confederate general and reputed grand dragon of the Alabama Ku Klux Klan.

As the people marched across the bridge those who looked up could see Pettus' name in big block letters emblazoned across the bridge’s crossbeam. Once they reached the top of the bridge a wall of state troopers could be seen stretched across route 80. They were wearing white helmets and slapping their clubs. Behind the troopers were deputies of sheriff Jim Clark, some on horseback, and dozens of white spectators waving Confederate flags.

“It would be detrimental to your safety to continue this march,” Major John Cloud called out from his bullhorn. “This is an unlawful assembly. You have to disperse, you are ordered to disperse. Go home or go to your church. This march will not continue.”

Marchers stood their ground.

After a few moments, the troopers, with gas masks affixed to their faces advanced and knocked the marchers to the ground and beat them with their clubs. The marches screamed in fear as the bystanders cheered. Then tear gas was dispersed and deputies on horseback charged ahead as they swung clubs, whips and rubber tubing wrapped in barbed wire.

After a few moments, the troopers, with gas masks affixed to their faces advanced and knocked the marchers to the ground and beat them with their clubs. The marches screamed in fear as the bystanders cheered. Then tear gas was dispersed and deputies on horseback charged ahead as they swung clubs, whips and rubber tubing wrapped in barbed wire.

Even though they were being chased, clubbed, whipped, had bones fractured and heads gashed, the men, women and children did not fight back.

Seventeen people were hospitalized during "Bloody Sunday" and television cameras captured the whole thing. When the footage aired that night, Americans were appalled.

Amelia attended two years at Georgia State Industrial College for Colored Youth (now Savannah State University). She transferred to Tuskegee Institute (now Tuskegee University), earning a degree in home economics in 1927. She also later also studied at Tennessee State, Virginia State, and Temple University.

In 1933, Boyton co-founded the Dallas County Voters League in.

In 1934 Boynton registered to vote. A few years later she wrote a play, Through the Years, which told the story of the creation of Spiritual music and a former slave who was elected to Congress during Reconstruction, based on her father's half-brother Robert Smalls, in order to help fund a community center in Selma.

After working as a teacher in Georgia, Boynton took a job as Dallas County's home demonstration agent with the U.S. Department of Agriculture in Selma. She educated the county's largely rural population about food production and processing, nutrition, healthcare, and other subjects related to agriculture and homemaking.

Boynton met co-worker Samuel Boynton while he was working as a county extension agent during the Great Depression. They both had an impassioned desire to better the lives of African-American members of their community. The couple would end up getting married in 1936 and have two sons, Bill Jr. and Bruce Carver. Bruce was the godson and namesake of George Washington Carver. Later they adopted Amelia's two nieces Sharon (Platts) Seay and Germaine (Platts) Bowser.

In 1954 the Boynton family met Reverend Martin Luther King, Jr. and his wife Coretta Scott King at the Dexter Avenue Baptist Church in Montgomery, where King was the pastor.

In 1963, Samuel Boynton died, but Amelia continued their commitment to improving the lives of African Americans. Boyton made her home and office in Selma a center for strategy sessions for Selma's civil rights battles.

In 1964 Boynton ran for the Congress from Alabama, hoping to encourage black registration and voting. She was the first female African American to run for office in Alabama and the first woman of any race to run for the ticket of the Democratic Party in the state. Although she didn't win her seat, Boynton earned 10 percent of vote.

The second of the Selma to Montgomery marches took place March 9th. King told hundreds of clergy who had gathered at Brown’s Chapel, “I would rather die on the highways of Alabama, than make a butchery of my conscience”.

King then led more than 2,000 marchers, black and white, across the Edmund Pettus Bridge. When they reach the other side, they were confronted by troopers and police who were blocking their path. King then stopped and asked the marchers to kneel and pray. After prayers, the troopers and police moved aside, but King and the marchers rose and retreated back across the bridge to Brown’s Chapel, believing that the troopers were trying to create an opportunity that would allow them to enforce a federal injunction prohibiting the march.

Later that night, after eating dinner at an integrated restaurant Rev. James Reeb and two other Unitarian ministers, Rev. Clark Olsen and Rev. Orloff Miller, were beaten by white men with clubs for their support of African-American rights.

Reeb born on January 1, 1927, in Wichita, Kansas, to Mae (Fox) and Harry Reeb. He was raised in Kansas and Casper, Wyoming. He attended Natrona County High School and graduated in 1945.

Even though his commitment to the ministry made it so he would be exempt from the draft, Reeb joined the army during World War II. After basic training, he was sent to Anchorage, Alaska as a clerk typist for the headquarters of Special Troops. He was honorably discharged eighteen months later in December 1946 as Technical Sergeant, Third Class.

Reeb became a minister, graduating first from a Lutheran college in Minnesota, and then from Princeton Theological Seminary in June 1953. Now he was an ordained a Presbyterian minister.

After this he accepted a position at the Philadelphia General Hospital as Chaplain to Hospitals for the Philadelphia Presbyter. To become a more effective counselor, he went back to school, enrolling at Conwell School of Theology, where he earned an S.T.M. in Pastoral Counseling in 1955.

On March 17th, the Federal District Court Judge Frank M. Johnson Jr. ruled in favor of the marchers from the suit filed on March 10th.

He took a job that would allow him to work closely with Philadelphia's poor community as a youth director for the West Branch Y.M.C.A. between 1957 and 1959. While at the Y.M.C.A. he abolished the racial quota system and started an integrated busing program to transport youth to and from the location.

On March 9th, King led the group of marchers to the far side of the bridge, where they were met with troopers and police. King stopped and led the protesters in prayer. Then the troopers moved aside, but King led the protesters back to the church.

President Johnson spoke out against the violence and urged both sides to respect the law.

On March 10th, the US Justice Department filed suit in Montgomery, asking for an order to prevent the state from punishing any person involved in a demonstration for civil rights.

The family was very poor and lived in one-room shacks with no running water. The schools Liuzzo attended did not have adequate supplies and the teachers were too busy to give extra attention to children in need. The family moved often and Liuzzo never began and ended the school year in the same place.

In 1941, Liuzzo's family moved to Ypsilanti, Michigan, where her father sought a job assembling bombs at the Ford Motor Co. Liuzzi's went to high school and after one year she dropped out and eloped at the age of 16. The marriage didn't work out and she moved back in with her family.

Liuzzo was notable for her protest against Detroit's laws that allowed for students to more easily drop out of school. She withdrew her children from school in protest. Because she deliberately home-schooled them for two months, Liuzzo was arrested and pleaded guilty in court and was placed on probation.

Reeb transferred to the Unitarian Church and became assistant minister at All Souls Church in Washington, D.C., in the summer of 1959. After three years of active service at All Souls Church, Reeb was fully ordained as a Unitarian Universalist minister in 1962.

In September 1963 Reeb moved to Boston to work for the American Friends Service Committee. He bought a home in a poor neighborhood and enrolled his children in the local public schools, where many of the children were black. His daughter Anne recollected that Reeb "was adamant that you could not make a difference for African-Americans while living comfortable in a white community."

In 1964, he began as community relations director for the American Friends Service Committee's Boston Metropolitan Housing Program, focusing on desegregation. Reeb and his staff advocated for the poor and pressed the city to enforce its housing code, protecting the rights of tenants of all races and backgrounds, particularly poor African and Hispanic Americans. The Reebs were one of the few white families living in Roxbury.

Reeb and his wife watched the coverage of Bloody Sunday on television. The following day, King sent out a call to clergy around the country to join him in Selma that Tuesday, March 9th. Reeb heard about King’s request from the regional office of the Unitarian Universalist Association on the morning of March 8th, and was on a plane heading south that evening.

Several clergy decided to return home after this symbolic demonstration. Reeb, however, decided to stay in Selma until court permission could be obtained for a full scale march, planned for the coming Thursday. That evening, Reeb and two other white ministers at at the restaurant and were beaten. The black hospital in Selma did not have the facilities to treat him, and the white hospital refused. Two hours later and Reeb finally arrived at a Birmingham hospital.

While Reeb was on his way to the hospital in Birmingham, King addressed a press conference saying that the attack was "cowardly" and asked all to pray for Reeb's protection.

Reeb had brain surgery and then went into a coma.

He died two days later from his injuries. His death provoked mourning throughout the country, and tens of thousands held vigils in his honor. President Johnson called Reeb’s widow and father to express his condolences.

On March 15th, Johnson talked about Reeb when he delivered a draft of the Voting Rights Act to Congress. That same day King eulogized Reeb at a ceremony at Brown’s Chapel in Selma. “James Reeb, symbolizes the forces of good will in our nation. He demonstrated the conscience of the nation. He was an attorney for the defense of the innocent in the court of world opinion. He was a witness to the truth that men of different races and classes might live, eat, and work together as brothers.”

Viola Liuzzo was horrified by the images the Bloody Sunday March.

She was born Viola Fauver Gregg on April 11th,1925 in California, Pennsylvania to Eva Wilson and Heber Ernest Gregg. Heber was a coal miner and World War I veteran. He left school in the eighth grade but taught himself to read. Eva had a teaching certificate from the University of Pittsburgh. Liuzzo had a younger sister named Rose Mary.

While on the job, Heber's right hand was blown off in a mine explosion and, during the Great Depression, and Liuzzo's family became solely dependent on Eva's income. Work was very hard to come by and Eva could pick up only sporadic, short-term teaching positions. The family decided to move from Georgia to Chattanooga, Tennessee, where Eva found a teaching position, when Viola was six.

Liuzzo experienced the segregated nature of the South firsthand. She realized the injustice of segregation and racism, as she and her family, in similar conditions of great poverty, were still afforded social privilege and amenities denied to African-Americans under the Jim Crow laws.

The Jim Crow laws were state and local laws that enforced racial segregation in the Southern United States. They were enacted in the late 19th and early 20th centuries by white Democratic-dominated state legislatures to disenfranchise and remove political and economic gains made by black people.

Two years later, the family moved to Detroit, Michigan, which was starkly segregated by race. During this time race riots erupted and Liuzzo and her family witnessed these horrific ordeals.

Liuzzo was working at a restaurant and had fallen in love with the manager, George Argyris. In 1943 they got married and then had two children, Penny and Evangeline Mary. That marriage didn't last more than a few years and the couple divorced in 1949.

Later Liuzzo married a Teamsters union buisness agent named Anthony Liuzzo. They had three children: Tommy, Anthony Jr., and Sally.

Liuzzo decided she wanted to go back to school to be a medical lab technician. She attended the Carnegie Institute in Detroit, Michigan. She then enrolled part-time at Wayne State University in 1962. She graduated with top honors, but worked for only a few months before she quit her job in protest over the way female secretaries were treated.

In 1964, she began attending the First Unitarian Universalist Church of Detroit, and joined the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). Liuzzo helped organize Detroit protests, attended civil rights conferences.

On March 16, Liuzzo took part in a protest at Wayne State. She then called her husband to tell him she would be traveling to Selma after hearing King call for people of all faiths to come and help. Despite her husband's concerns, Liuzzo Left her children in the care of family and friends, she contacted the SCLC who tasked her with delivering aid to various locations, welcoming and recruiting volunteers and transporting volunteers and marchers to and from airports, bus terminals, and train stations, for which she volunteered the use of her 1963 Oldsmobile.

On March 19th, Wallace sent a telegram to President Johnson asking for help.

On March 20th, President Johnson issued an executive order federalizing the Alabama National Guard and authorizes whatever federal forces the Defense Secretary deems necessary.

When Liuzzo and Moton stopped at a red light, a car with four members of the local Ku Klux Klan, including FBI infiltrator Gary Rowe, pulled up alongside her. When they saw a white woman and a black man in a car together, they followed Liuzzo.

Liuzzo's funeral was held at Immaculate Heart of Mary Catholic Church on March 30 in Detroit, with many prominent members of both the civil rights movement and government there to pay their respects. King and Jimmy Hoffa were some of those in attendance.

Liuzzo's husband and children became victims. They received hate mail and phone threats and had a cross burned on their lawn. The KKK told awful likes about Liuzzo, and these were repeated in FBI reports.

On March 21st, the third of the Selma to Montgomery marches began. About 3,200 people, including King, marched out of Selma for Montgomery. They were protected by 1,900 members of the Alabama National Guard under federal command, and many FBI agents and federal marshals. They marched for about 12 miles and then slept in fields at night. Liuzzo marched the first full day and returned to Selma for the night.

The marchers arrived in Montgomery on March 24th. Liuzzo rejoined the march four miles from the end, where a "Night of the Stars" celebration was held the City of St. Jude with performances by many popular entertainers of the day, including Sammy Davis, Jr. While there, Liuzzo helped at the first aid station.

On March 25th, the Liuzzo and other marchers arrived at the Alabama State Capitol building, with a Confederate flag flying above it. Martin Luther King addressed the crowd of 25,000, calling the march a "shining moment in American history."

After the march, Liuzzo, assisted by Leroy Moton, a 19-year-old African American, continued shuttling marchers and volunteers from Montgomery back to Selma in her car. As they were driving along Route 80, a car tried to force them off the road. After dropping passengers in Selma, Liuzzo sang strains of the civil rights anthem, “We Shall Overcome,” as she turned her Oldsmobile back toward Montgomery for another carload of marchers. They then went and got gas and they were subject to abusive and racist calls.

“These white people are crazy,” Liuzzo said as she pressed the accelerator in attempts to out run them.

Both cars were racing down the highway at 100 miles per hour. Sadly, the KKK overtook the Oldsmobile and pulled up alongside. Liuzzo turned and looked straight at one of the Klansmen, who sat in the back seat with his arm out the window and a pistol in his hand. He fired twice, sending two .38-caliber bullets crashing through the Oldsmobile window and Liuzzo’s head, mortally wounding her.

Moton grabbed the steering wheel and hit the brakes, and the Oldsmobile veered into a ditch, crashing into a fence. The KKK came back to inspect their work. Moton was covered in blood, but he was relatively uninjured. He had to pretend to be dead while they shone a light in the car. As soon as they left, Moton flagged down a truck carrying more civil rights workers.

Liuzzo had a close relationship with an African American woman named Sarah Evans. After initially meeting in a grocery store where Liuzzo worked as a cashier, the two kept in touch. Evans eventually became Liuzzo's housekeeper while still maintaining a close, friendly relationship in which they shared similar views, including support for the civil rights movement. After Liuzzo's death she stayed and helped take care of the children.

Her children were fiercely proud of Liuzzo, and tried to sue the FBI for lying about her (the case was thrown out of court). Her home newspaper came to Liuzzo's defense.

“We cannot wish mercy to those who have passed a judgement of hate upon her. They have found the only possible way to alienate a forgiving God. … We (pray) for rest, peace and light to Mrs. Liuzzo. Maybe she has finally found a life free of prejudice and hate.”

President Johnson was enraged at Mrs. Liuzzo’s murder, and he ordered Congress to start a complete investigation of the Ku Klux Klan.

The four Klan members in the car—Collie Wilkins, FBI informant Gary Rowe, William Eaton, and Eugene Thomas —were arrested within 24 hours. President Lyndon Johnson appeared on national television to announce their arrest and tried spin the FBI's involvement in a positive way.

Wilkins, Eaton, and Thomas were indicted in the State of Alabama for Liuzzo's death on April 22nd. FBI informant Rowe was not indicted and served as a witness. Rowe testified that Wilkins had fired two shots on the order of Thomas.

On May 26th, the voting rights bill was passed in the U.S. Senate by a 77-19 vote. After debating the bill for more than a month, the U.S. House of Representatives passed the bill by a vote of 333-85 on July 9.

Johnson signed the Voting Rights Act into law on August 6th, 1965, with Martin Luther King Jr. and other civil rights leaders present at the ceremony.

Johnson signed the Voting Rights Act into law on August 6th, 1965, with Martin Luther King Jr. and other civil rights leaders present at the ceremony.